In April 2008, Purulia Pumped Power Storage Project was launched on the Bamni River in the slopes of the Ajodhya Hills near Baghmundi, despite protests by the local communities. Recently, work has commenced to establish yet another Pumped Power Storage Project, within 3 kms of the earlier PPSP. Already reeling from the effects of the PPSP, local tribal communities and the entire ecosystem of the area, are today faced with a fresh round of severe disaster in the making. Kaushik Mukherjee and Sourav Prokritibadi write about details of the project, and the kind of havoc that the greed of a few is going to wreak with the lives of lakhs of people in the years to come.

“Kotto jongol chhnirbek! Sohoje ee jongol chnirte lairbek” [‘How many trees are they going to cut down? These forests can never be destroyed so easily’] – comment by a tribal lady, Marang Buru hills, Ajodhya, Purulia.

The hilly area of Ajodhya is located within the dry deciduous forest belonging to a sub-region of the north-eastern part of Chhotanagpur plateau, included within a distinctive agro-ecological zone of West Bengal—the undulating red and laterite zone. Some of the prominent and well known hills of this area are Mathaburu, Gorgaburu, Pakhipahar, Ajodhya. The distinctive geological-hydrological backdrop and its characteristic floral and faunal diversity supports a local human population—who, as official documents testify, are dependent on the forest for their life and livelihood. Moreover, the topography, forest wealth and wildlife attract tourists, wildlife researchers and naturalists in considerable numbers. Apart from being a popular tourist destination, Ajodhya hill range is significant for the entire Santhal population of all over India itself. The area is located precariously close to excavation sites that have yielded a rich outcrop of microliths—pushing the prehistory of Bengal back to 42,000 years BP (“Before Present”) and promoting the area to the status of one of the most sensitive archaeological locales in West Bengal.

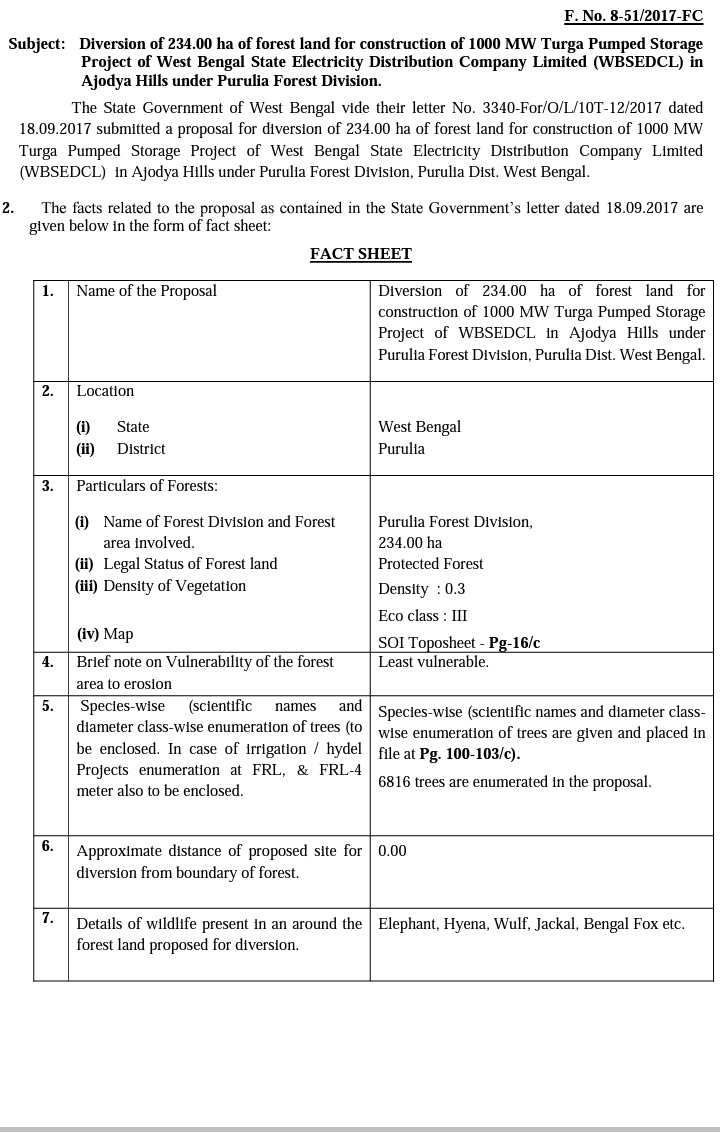

Ajodhya Pahar became important in terms of electricity generation for the first time in 2008. On 6th April 2008, Purulia Pumped Power Storage Project (PPSP, hereafter) was launched on the Bamni River, downstream of Bareria village, in the slopes of the Ajodhya Hills near Baghmundi. The project inaugurated by then chief minister of West Bengal, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, was undertaken in collaboration with Taisei Company of Japan and involved an investment of around 2953 crore. The project claimed to generate 900 megawatt of electricity with help of four reversible turbines of 224 megawatts each. There is another river located at a linear distance of 2.5 to 3 km from the Bamni River called Thurga. Recently, work has commenced to establish Thurga Pumped Power Storage Project (TPSP, hereafter) on it. TPSP is, declaredly, the second project in a preconceived overall plan of four pumped storage schemes in the Ajodhya Hills. However, no names or locations were mentioned. In the Factsheet prepared by officers of the Forest Department of Govt. of West Bengal, which came up for consideration for the Forest Clearance, the four projects mentioned are Purulia Pumped Storage Project, Thurga Pumped Storage Project, Kathlajal Pumped Storage Project, and the Bandu Pumped Storage Project. However, there is some confusion as to which exactly are the third and fourth projects. Another important source mentions Bandu as the third project and Kulbera (or Kurbera) as the fourth pumped storage project in the Ajodhya Hills, with Kathlajal taking a backseat due to some difficulties in implementation in a reserved forest area.

But the key questions are:

I. How feasible is it to build 4-5 power plants in a hilly area like Ajodhya?

II. What are the possible impacts of this kind of projects on the unique ecology and biodiversity of the Ajodhya Hills? How are the endemic flora and fauna going to be affected by this project?

III. How would these projects impact the rich traditional local culture of this area?

IV. How are these projects going to change the lives of people in about 75 villages?

V. What would be the impact of this project on the neighboring regions?

I. Feasibility

PPSP is completed and its project locations are actual geographical facts. Furthermore, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA hereafter) of the TPSP provides the location of the Upper and Lower Dams (Reservoirs). One can see that the distance between the two upper dams of the two projects is 2.71 km and distance between the two lower dams is as small as 2.33 km. It is clear that the two projects are situated very close to each other. The exact proposed locations of the project sites of the Kathlajal project are unknown. However, the Kathlajal Nala is situated within 6 km geodesic distance of the Kistobazar Nala and towards its east and south, as the Thurga is to its west and north. In terms of the location of the Bandu Nala and from what one has come to learn of the upper dam and lower dam coordinates, it appears to be situated on the northern side of the Ajodhya Hills. Of the Kulbera project, little seems to be known about its location except it is to be undertaken somewhere in the Ajodhya Hills area.

The project of hydroelectric power generation from the Bamni River started in the year 2002 and ended in 2008. Unlike other hydroelectric power projects, these types of power plants don’t need an abundant flow of water. Rather, they can work on a lesser supply of water, to the extent that they are equipped for power generations from dry and arid areas. Firstly, a dam is constructed on a river with one reservoir at a higher elevation and a second reservoir at a lower elevation within a distance of about some hundred meters. The usual mechanism of power generation is applied as water held in the higher reservoir, is released through a turbine to the lower reservoir. However, it is important to note that the turbines of the Pumped Storage Projects are reversible. And since there is little regular natural supply of water to the higher reservoir, the water has to be pumped back to the higher reservoir, using electricity, to maintain the required amount of water upstairs. Sometimes, the electricity used in this exercise is more than that of the amount that had been generated primarily at the time of releasing the water from the upper reservoir. This demand of electricity can also be fulfilled by other power stations nearby. This naturally invokes the question of whether any excess electricity is generated at all from these projects. Especially, the 900 megawatts of electricity in PPSP seems to fail to strike a balance between the production and expenditure of electricity in terms of the aforementioned functioning of the dams. In fact, it also seems that instead of efficiently generating power while the water is pumped to the higher reservoir, it ends up in holding a huge amount of water in the latter so that it can be released immediately through the turbine in moments of urgent ‘needs’. So, it is unlikely that these projects will provide a continuous flow of electricity or meet the local people’s needs at any terms. On the contrary, they are more suited to ensure an immediate supply of power to well electrified urban areas at moments of scarcity or high demand. There shouldn’t be any power scarcity even for a moment while a doctor operates in a hospital, but unfortunately every other kinds of necessities have been known to take a back seat in comparison to ‘needs’ like celebration of IPL games.

What are the other possible problems that Ajodhya hills could face following completion of this project?

Impacts of construction of the two reservoirs (one at the higher elevation and the other at the lower) are significantly different from that of an ordinary hydro electric power plant, as the former requires:

i. Acquisition and diversion of almost twice the amount of agricultural and forest lands in terms of land use.

ii. Twice the amount of investment is needed.

iii. Large amount of materials needed for the extensive construction works and problems like their transportation and disposal negatively affects the entire local ecological balance.

iv. Construction of multiple dams in an already water scarce area will lead to even more heightened problems of water crisis.

v. Small seasonal rivers stand a continuous risk of running out of water.

vi. Deforestation and construction works on small hill ranges like the Ajodhya hills, can lead to increased risks of soil erosion and landslides. These risks become more prominent due to continuous mining and quarrying activities in the hills.

All of the aforementioned problems have already started to become prominent in the Ajodhya hills. Extensive ‘development activities’ in a small geographical area (covering only a few kilometers) pose the entire local ecology with grave challenges. The Thurga Project will itself engulf 292 hectare of land, out of which 234 hectare is forest land. These four similar projects will claim at least 1500 hectare of land including about 1000 hectare forest land in total.

II. Impact on Ecology and Biodiversity

The government website of the Purulia Zilla Forest Department states the following-

“Bio-Diversity: Biogeographically it represent zone 06B (Deccan Peninsula Chhotonagpur), Mammal – 39 species (5 in Schedule – I) – (Pangolin, wolf, leopard cub, leopard, elephant). Amphibian – 9 species, Fish – 27 species, Mollusk – 9 species. Most interesting is the Madras Tree Shrew which is found on the top hills of this ecosystem and nowhere else in West Bengal. Ajodhya hill ecosystem hosts few number of mega-mammals like elephants. Though the major elephant habitat is engulfed by PPSP, at present, the number of such resident elephants is considered to be 8 to 10. Apart from that the seasonally migrated herds of elephants from nearby Jharkhand forests took shelter in this area for days together in different seasons of the year.”

“The establishment of a hydro-electric power project in the Ajodhya Hills near Baghmundi has affected the elephant population in Ajodhya Hills and the usage of this corridor”, says a report by the Wildlife Trust of India. These kind of claims are made not just in the documents of the Forest department itself, but also in the Forest Advisory Committee’s (FAC) report.

The Forest Department website further states – “Ecological Importance: The total area drains into two major river systems, namely Subarnarekha and Kangsabati. Ajodhya hill plays an important role in harvesting of monsoon rain. Moreover, few lakhs of people residing in and around the forest directly or indirectly depend on this forest for fodder, fuel wood, small timber and other tangible or intangible benefits. Small dams like Murguma, Pardi, Burda, Gopalpur, Tilaitar helps in irrigation of agricultural field.”

These are the facts put forward by the government at least till September 2018. Let’s see what was the biodiversity scenario of these areas before a few decades. For instance, the list of mammals as obtained from the Government Gazzette are as follows-

“Leopard, Jungle Cat, Leopard Cat, Hyena, Wolf, Jackal, Fox, Black/Sloth Bear, The common otter, Indian Civet, The Indian grey mongoose, Wild Pig, Sambar, The barking deer (muntjac), The four horned antelope, Common Hare, Rhesus Macaque, Langur, The short-tailed Indian pangolin, The striped squirrel, Porcupine, House mouse, House rat, House shrew, Bandicoot rat, Yellow bat, Flying-fox”.

This unique biodiversity has already faced much destruction and losses. Wildlife has either been slaughtered or driven away to speed up the construction process of PPSP. As one local club member says, “Bombs were hurled to kill and get rid of the animals for the construction of PPSP. There even have been such incidents where meat attached to a bomb was used as a bait to kill the leopard cats.” It should be noted, that the Government reports suggest that the area gives shelter to at least five kinds of mammals who belong to schedule one category (critically endangered). Providing protection to those animals is then the constitutional responsibility of the Government. Among the other mammals, the condition of the elephants is crucial to take note of. A herd of twelve to fourteen elephants reside in this place. Although the ecology has been degraded and endangered, these troops of elephants will have nowhere to go if they lose this last piece of tiny area.

“Panchayat has been planting thousands of Eucalyptus trees in the Ajodhya hills. But eucalyptus has been proved to be damaging to entire local natural ecology, as it exhausts ground water and soil nutrition. Even grasses do not grow under these trees”, states a teacher of Teliabhasha village. Actually, the concerned forest needs more protective, empathetic care rather than further damage. Moreover a project that, among other things, necessitates abundant stone quarrying in an area of major archaeological concern is, to say the least, a hugely worrisome proposition.

PPSP has resulted into the cutting down a forest of about three and a half lakhs of trees (where the upper dam of Ajodhya is now situated). In spite of the promise of compensatory afforestation, for ‘offsetting biodiversity’, not a single tree has been planted so far in Ajodhya or Bundwan. Although the government report on tree felling claims that only six thousand trees will be cut down, Thurga Project is estimated to shatter around four lakh trees. “They (the govt. officials) only value artificial artifacts. How can they appreciate anything that is natural?”, sighs Janashyam Murmu. Supposedly, the compensatory afforestation for TPSP is going to take place in three places of Purulia and in a single block of Jalpaiguri in North Bengal. However, nothing has been specified about the name of the blocks or the kind of land use (cultivable or forest or residential) present there.

Posted by Sourav Prokritibadi on Friday, 28 September 2018

III. Impact on Local culture and tradition

Near the village panchayat of Ajodhya, lie Sutantandi and Sitakunda, sacred grove and culturally significant to the local Santhal people. Sitakunda is the place where in an annual festival, lakhs of tribal people meet and celebrate unison. Sutantandi, on the other hand is resorted to resolve matters of the commons. “Sutantandi is our Supreme Court; we abide by all the decisions taken there. Previously the place was covered by trees that hardly let any sunlight in. However, Forest Department has cut down many age old trees. We demanded protection and conservation of Sutantandi for it to lay untouched”, states Jhulan Murmu. There are many sacred places of MarangBuru in the forest areas. Besides, there is the sacred MarangBuru hill, most of which is about to be submerged under water if the dam construction takes place.

IV. Impact on lives of people

PPSP offered jobs to only a few people and those too were temporary contract jobs. Those jobs were over as soon as the construction was completed. The villagers of about seventy villages therefore face an intense problem in terms of livelihood. On one hand, they face scarcity of water, while trying to meet the basic needs for cultivation in the fields, as all the river water are drawn to the power projects. On the other hand, large tracts of cultivable land and forest areas are immersed in the reservoir water of the dams. There are about two hundred non-local people with permanent jobs from PPSP. Considering standard, four such projects would employ eight hundred people, while robbing livelihood for people in more than seventy villages. These people will be forced to become ‘development refugees’ or ‘ecological refugees’ and forced to move to urban areas as ‘footloose’ or migratory labour, engaged in precarious activities.

“I have some cattle. Other than that, rice is cultivated just beside the Thurga River in the summers. I did not leave the place, but my sons had to. This (TPSP) will be a hard blow to any hopes left for the place and the people here. There would be no option other than to go to Bombay or Chennai and work as casual labor”, remarked an elderly man standing on the Upper-Dam Co-ordinates of the Thurga River basin.

V. Impact on Neighboring areas

We can pick just one single example out of many that will affect the neighboring areas due to these projects. For example, the rivers affected by the first and the proposed second project, flow into the same river, the Sobha, which in turn flows into the Subarnarekha. It is not that difficult to understand that these projects will surely affect the flow and volume of water in Sobha River and subsequently in Subarnarekha River (132.9 kms away from Ajodhya hill) as well. Kartik Tudu said, “Previously, digging up to seven to eight feet near the river would fetch us water whereas now it is not found even below ten feet after PPSP was launched.”

The TPSP has unjustifiably received Environmental Clearance. A careful look at the EIA and the Social Impact Assessment (SIA) reveal that the basic approach to evaluating impact is insincere, misdirected and faulty. Therefore, the proper picture of real impact on the environment and the people dependent thereon has not been portrayed.

It is no surprise that the EIA simply avoids taking into consideration the impact of the previous project, the PPSP situated on the Kistobazar Nala, located very close to the Thurga Project, with the distance between the two lower dams being about 2.33 km and the distance between the two upper dams being about 2.71 km. As the map of the area clearly shows, both the projects are situated in the same area of forested land and natural terrain and their impacts will inevitably combine to affect the area in question. Taking into consideration the impact of the already operational project since its inception and operation was the obvious appropriate thing to do. But, this was precluded by the Terms of Reference.

A group of professors from Vidyasagar University wrote in the EIA report on the ongoing project of PPSP—“It cannot be presaged how much these Pumped storage Projects will improve the level of peak power scenario of West Bengal, but from the above study it is obvious that PPSP has caused a great damage to the environment and economy of the study area. Cost benefit analysis also shows that this type of project in this drought prone region is not economically viable if we consider the intangible costs that the society and environment have already paid. Therefore, immediate mitigation measures are required to restore environmental stability and ensure economic prosperity of this region”.

“What is this dam for? What about our sustenance? We get our food from the hills. Forests provide us with woods and food. If Baghmundi is submerged, what are we supposed to eat? We will die. Think about this, and also inform the government”, exclaimed an elderly woman of Shaldi village, while watching pieridae butterflies, sitting on the banks of the Thurga.

When the people of the Ajodhya hills were made to sign in the No Objection Certificate, they were not given any proper information about the project at all. How? A villager informed, “They were distributing snacks in the Panchayat office. When we went to collect the food, they made us sign first”. Another said, “I was made to sign when I went to collect the ‘Swastha- Sathi’ (health scheme by govt. of WB) card”. “A ‘Memsahib’ came for our meeting. When we went to see her, we were asked to sign”. “They said that there will be a project. We demanded permanent employment, if the project commences. DM asked his people to write down all our demands. We signed only after we saw our demands on paper”.

All the villagers from Ranga, Tarpania, Teliabhasha, Hatinada, Barelahor, Chhatni and Kalijhorna, who shared their experiences with us, later understood the actual extent of problems and called for village meetings and put forward their grievances as a resolution (Gramsabha is still not functional here in accordance with the Forest Rights Act, 2006)

Following is a leaflet published by the affected villagers:

“Few years earlier, when the project of Purulia Pumped Storage (hydro-electric power generation unit) was started, not only were we promised with jobs but also the option of being able to avail the generated electricity free of cost. However, the electricity generated by the project found its way to Arambag and Ranchi, leaving the local place (Ajodhya hills) the way it was. Of all that we got from the project were some contractual jobs, that too temporary in nature. Now we have to live with the fear of the disturbed and displaced elephants invading our homes and crop-fields. It was the most natural reaction of the flock after facing frequent destruction of their habitats and dearth of food. We also clearly remember the death of an elephant, electrocuted by the high tension wires, near the Kashidi dam two to three years ago. The human interventions not only affect the elephants but also other wild animals which inhabit these places. We have also noticed a significant decrease in the population of the rabbits, pangolins, bears and deer which previously used to exist in abundance. Some of them like the jackals, varied kinds of indigenous leopards and snakes also tend to attack our homes, in response to their own crises. This antagonism, we fear, will increase if the Thurga Project is undertaken.

Additionally, the Bamni River has been extirpated due to the Purulia Project. We already face an immense problem of drawing water to our fields for cultivation; the Thurga Project will only contribute to the aggravation of this problem.

Both the adivasi and non-adivasi people inhabiting this place share an inseparable and inexplicable relationship with the forest. Ranging from gathering dry leaves for fuel, making structure of our homes and cultivation equipments like tillers from the wood, the ghong leaves that protect us from heavy showers, to the chosen trees that organically witness our marriages – the forest offers us our living. We also get to sell some of the Kendu leaves that we gather from the forest. The forest grass is the only place for our cattle to graze. In the course of such events, they have also been deprived of their grazing lands due to such projects. Where will we go if they cut off our sacred grove of MarangBuru?

The Purulia Project stripped Ajodhya off about three and half lakh trees. The promise, however, of planting trees back (‘compensatory afforestation’) in Bundwan (another block of Purulia) remains unwarranted. On the other hand we were alleged of theft when our villagers went to see the modern machines used during the Purulia project. The loss of medicinal plants in this process is profuse and cannot be supplemented ever. Wide roads have been constructed after clearing off these forests, but there is hardly any concern regarding the possibility of the functional relationship between the dearth of forest cover in the hilly areas and the irregular and decreased rainfall. We fear the environmental conditions will deteriorate if such activities continue. This deterioration also, by default, puts our life at stake.

One of our sacred places of Sutantandi lies within the Ajodhya village panchayat which deserves to stay without any intrusion. For its conservation and to protect it from appropriation, we demanded a declaration of the area to be under reservation. While we witness Thurga Project demanding lands from the village panchayat, the Government stays non-vocal about our demands of the reservation of Sutantandi.

As per 3rd and 5th clauses of Forest Rights Act (FRA, 2006), we did not agree to any project which would harm our forests, which belong to everyone in our GramSabha and which we have now sustained over generations. Any project involving deforestation and felling of trees in these forests directly violates the FRA (2006) as it undermines our rights to these forests as well as our common cultural heritage. On the basis of the 5th clause of the FRA, we hereby declare the deforestation project in Ajodhya hill as illegal. We demand that any such projects undertaken by the authority be stopped immediately. Besides, we would also like to point out, that the members of our village were not adequately informed by the government on the terms and clauses of FRA. In fact, FRA has not been implemented in our area at all. This also violates the 2009 guidelines of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. These central government guidelines state, as long as the communities living in the forest areas object to diverting the forest lands for any other uses or projects, such projects can never be undertaken. For any such project, written mandate of the concerned GramSabha (consisting of the villagers living in these areas), is needed. Since we did not agree to this deforestation of Ajodhya hill and our GramSabha was kept into dark about any such project undertaken, any implementation of this project is illegal. We did not even get a chance of a public hearing and proper information. Considering all these issues we do not want Thurga project in our locality.”

“There is no use of contemplating the matter with coherent set of arguments and counter-arguments. The electricity or any important service hardly matters to them; it’s only the business of selling some construction materials that they are interested in! It ends up inflicting immeasurable harm to the rivers”, said a Professor of the Indian Statistical Institute.

Let's try to ecologise ourselves. Let's try to save Ayodhya hills. Let's try to save ourselves. Plz tag your friends.

Posted by Kaushik Mukherjee on Monday, 17 September 2018

We conclude with the following open questions:

i. Although the project is claimed to electrify the local villages, the proportion of villagers enjoying this facility is extremely low. Whatever power supply is available in the local villages, it is very irregular and non-reliable. However, in the cities, electricity is often wasted away in luxuries like shopping malls, air conditioners and many other non-necessities. Even as new electricity is promised from these projects, we should ask, who is it promised to? If the new electricity generated in our lands is used to light up Ambani-Adani’s mansions, why can’t these projects be built on their own grounds?

ii. Is the business of construction materials really the sole driving force for these projects? Or does it involve a taming and domestication of the natural ecology keeping growth of maniac-development induced tourism business in mind, even if it results in massive ecological degradation?

iii. How relevant is the concept of ‘biodiversity offsetting’ in the face of this colossal ecological footprint?

iv. Is not any kind of Power Projects (In Plains or in Mountains) inevitably catastrophic to the rivers and the environment as a whole?

v. If law can be used to bypass every form of community rights, assuming that the subaltern can not speak for themselves, then why is it so necessary to make new laws and acts for protecting forest rights?

The authors acknowledge the contributions of S. Chakraborty ar a resource person, and the suggestions and inputs of Iman, Suchishree, Mekhla in writing of this article. Names of villagers quoted in the article have been changed to protect their identity. Photos are courtesy authors.

In 2013 , I had an opportunity to enter the inside of the plant under ground. The project engineer in charge has indicated that there a good numbers of natural springs in the ayodhya hill region which are good for establishing another 4 nos of such power projects. Now, reading this article it is obvious that govt is going to do so. The employee of the ppsp is now in colony beneath the hill and employees of others 4 projects also soon be such colonies nearby . It will eventually add a tag on tourism .Hill top will gradually be occupied by the people marowari for hotel businesses. The land the forest of hill ranges which has been look after by local 70 villages will be driven away gradually by the out siders, tactically .

Govt should think about balancing the both the people and projects. Industry is needed for progression but people’s plight also need due importance.