Shantanu Kamble is one of the most powerful yet one of the least discussed shahirs of our times. His songs are about the Dalit lives and Dalit struggles, the history of discrimination and exploitation and the call for resistance. In these times when anti-caste political workers are being hounded by the State, when poets and singers are being arrested for singing songs, when the word ‘Dalit’ itself is under attack by the powers that be, we remember Shantanu’s poems – for truth, courage, self-respect and love. Aisha Kawalkar writes.

The legacy

Maharashtra has a tradition of shahiri that is several centuries old. Powadas (ballads) are a traditional art form involving oral rendition of history with the aim of invoking inspiration and pride. The lead performer who writes, sings and also acts as a narrator is called the Shahir. Dalit movement in Maharashtra has time and again reinvented the shahiri tradition to mount a critique on the social injustice inherent in a society fractured by caste, class and patriarchy. In the Jalsas (cultural programs) by Phule’s Satyashodhak Samaj, in 1890s, popular folk art forms were employed to put forth an alternate, non-Brahminical history and foreground social evils such as superstitions, untouchability, oppression of women and peasants. During the times of Ambedkar, Jalsas became more explicit than ever in spelling out the message of opposition to caste-based oppression. They also raised voice against vices like dowry, prostitution in the name of religion, indebtedness, and underscored the need for education, organised effort and struggle. Jalsas continued to gain in popularity and importance after Ambedkar’s death, with songs about his life and work. Over the course of the journey that will soon complete a century, many Ambedkarite shahirs have helped hone shahiri as an anti-caste tool and have kept the Dalit consciousness alive amongst the masses.

With increasing industrialisation, some shahirs who wrote and sang about the worker class, labourers and people of the streets, came to be known as Lok Shahirs (people’s poets). Notable amongst them are Annabhau Sathe, Amar Sheikh, Wamandada Kardak, Vilas Ghogre, Namdeo Dhasal, Sambhaji Bhagat and others, who have written and performed towards the cause of the downtrodden and earned a name for their fierce poetry and singing. They are alternatively referred to as “Vidrohi” shahirs (rebel or resistance poets). Shantanu Kamble was a powerful artist and activist who belonged to this tradition and left an indelible mark on the Ambedkarite movement with his poignant poetry and writings.

Shantanu’s fiery style of shahiri

“Dalitare halla bol na, Shramika re halla bol na”… this was Shantanu Kamble’s first, popular song penned after the Khairlanji massacre to express his pain and angst over the atrocities on Dalits. He recalls in it, the horror of mass killings at Ramabai Nagar (1997), molestation and rapes of Dalit women for caste domination and torching of Dalit colonies. In the same song, he also draws attention to how the state, its machinery and its nexus with the capitalists works against the marginalised.

Dalits raise your voice, labourers raise your voice!

This democracy is not yours

The establishment is not yours

The justice system is not yours…

These systems, since centuries, were never yours

where religion is used as opium (to lull you) and caste as its weapon

Fight this weapon with your bare hands, take control of the power

This song illustrates the features of Shantanu’s songs. He uses the folk genre along with radical content with the aim of not entertaining but ‘disturbing’ – for voicing dissent and challenging the establishment, to not just perform but to unite people for resistance. His lyrics are a straightforward, unveiled war-cry against caste and class oppression, unbridled capitalism, and state repression. After this song he continued to write through prose and poetry, about the incidents of caste violence, as and when they happened, laying bare the apathy of the state. For instance, in another candid verse, he up-front questioned, the then President Abdul Kalam about his silence over the riots that followed the Godhra incident and over the mob lynchings of dalit youth in Jhajjar.

His repertoire of songs also included varied forms like heart-wrenching ‘lullabies’ for the child that goes to sleep hungry and love songs like “Samtechya vatena, khankavit painjan yaava, tu yaava, bandhan todit yaava…” (Through the path of equality, with your anklets clinking, you should come… breaking all shackles of social prejudices and norms). Many a times, the protagonist in his ballad is a woman and is an equal, fearless fighter in the struggle for liberty, for example when she says, “Udya tya sarkarla jaab vicharayla jayin, cchakula bandhun paathila, haati hatyaar ghein” (for all the injustices we are facing, I will confront the establishment, carrying my child on my back, I will be up in arms). Characterised with simple yet fierce and ‘disturbing’ language, easy and catchy tunes, the intertwining of emotions and thoughts, guided by the principles of Buddha, Kabir, Phule, Ambedkar, Bhagat Singh and Marx, the songs of this rebel poet have been sung widely in the progressive movement.

कौन आझाद हुआ?

उठो साथियों आओ हटके, ना सफल हुई लढाई रे

जैसी आझादी चाही थी, ना वैसी आझादी पायी रे

शहीदों का तो सपना था यहाँ शोषण कभी भी होए नहीं

सेठों के हाथों में सत्ता यहाँ कभी भी जाये नहीं

आज सेठोंका बाजे डंका, रोये भारत माई रे

दलित मजदूर किसान आदिवासी जागो भारतवासी रे

नई आझादी के लिए फिर से लढाई लडनी रे

(We fought for freedom but we never got free. The power just got transferred into the hands of the the casteist, the capitalists. We have to fight together for a new freedom.)

Introduction to the movement

Being born in a landless, farm labourers’ family in a village in Sangli and later while growing up in the slums of Wadala in Mumbai, Shantanu witnessed poverty and caste discrimination first hand. As a young adult he took whatever odd jobs came his way to provide for his family; he worked as a labourer, a ward boy in a hospital, contract worker in private companies. Through his experiences – of a meager salary, no regular work, illnesses due to living conditions that caused absenteeism at work for which he would be thrown out of work without salary dues – he saw through the exploitative, capitalist economy and it’s inherent contradictions. Shantanu did his schooling up to class X but he kept learning through the life he lived. He later did a para-professional social work course which led him to work in NGOs like Child Line, Youth and Media Matters. It was his work and interactions with some activist youth in his basti that brought him in contact with the progressive movement and he soon became an activist himself. With a “duff” (tambourine) in his hand, he would sing in zeal the songs of Lokshahirs and soon himself started penning songs of resistance.

Why sing and perform for resistance, rather than engage directly in political action?

“Political revolutions have always been preceded by social and religious revolutions”, Babasaheb Ambedkar pointed out. Following this principle, Shantanu dedicated his life to provide expression to such a cultural resistance towards conscientisation. “Culture is the medium to take our thoughts to the people,” said Shantanu, underlining the role that cultural activism plays in the fight against “fascist forces”.

As theater critic, theoretician and political activist Antonio Gramsci explains, political power rests upon cultural hegemony. Therefore, part of any revolutionary project is creating a counter hegemonic culture. Ambedkarite activists have understood this well and have been using performing arts to create social and political consciousness, to effect change within and outside, to “educate, agitate and organise”. Also, using music as a way of collectively perceiving and understanding the world and the oppression within it, shahiri has helped people to heal by articulating the pain and the yearning for anticipated liberation.

Samata Kala Manch and Kabir Kala Manch cultural workers, together with journalist Nikhil Wagle, activist Vira Sathidar, retd Justice Kolse Patil and Deepali Wagh, partner of Lokshahir Shantanu Kamble. Photo: GroundXero

His contribution to the movement

Apart from being a dedicated cultural activist himself, Shantanu also played a prominent role in nurturing the progressive movement. He was one of the founding members of the Kabir Kala Manch and the Republic Panthers Caste Annihilation Movement which have an emancipatory political framework, highlighting the nexus of caste and class as one of the primary realities of the society. Being a strong critic of both the traditional Left and the mainstream Ambedkarite movement, Shantanu held that while the left has historically refrained from involving in issues related to caste, women and the minorities, using class as the only framework for oppression, the Ambedkarite movement has also narrowly focused only on caste, ignoring that caste is inseparable from the economic structures of a capitalist society. He implored both the fronts to form a common vision and work together, “लोकशाही क्रांतीचे उठवा की वारे, भिम सेना लाल सेना एक व्हा रे सारे” (To revolutionise democracy, work together Bhim Sena and the Red Army).

Shantanu was foremost in mentoring cultural squads in various districts of Maharashtra, and teaching them how best to use the local, traditional repertoire of the region to create political consciousness among the people. He was involved with Vidrohi Sahitya Sammelan, set up in the late-1990s, as a counter stage to the state-sponsored Marathi Sahitya Sammelan which, as critics point out, was dominated and controlled by upper-castes, and awarded only upper-caste authors. He was also one of the writers and editors of the magazine “Vidrohi”. Later on, he actively took to social media to voice his thoughts. In fact the mainstream cultural industry too could not ignore Shantanu for long. The 2014 national award-winning Marathi movie “Court” was based on Shantanu’s life. His friend, activist Vira Sathidar played the lead character of Narayan Kamble in the film that depicts the persecution of activists like Shantanu against the backdrop of an indifferent legal justice system.

Repression by the state

Cultural resistance by artists has often met with state hostility. In 2005, Shantanu was accused by the Nagpur police of having Naxalite connections and charged with sedition and waging war against the state. What was the evidence? He wrote and sang “like Gadar”, alleged the prosecution. After 100 days of police custody, he was granted bail and subsequently, acquitted of all charges. But, the incarceration, physical and mental torture – and the life-long relentless struggle for survival – had a lasting impact on his body. Shantanu died on 13th June this year, at the age of 39, after prolonged illness. This was, incidentally, within a week after his comrade Sudhir Dhawale along with 4 others were arrested by the Pune police and slapped with UAPA on the charges of organising the 200th anniversary of the Bhima Koregaon battle which has been a symbol of anti-caste movement in Maharashtra.

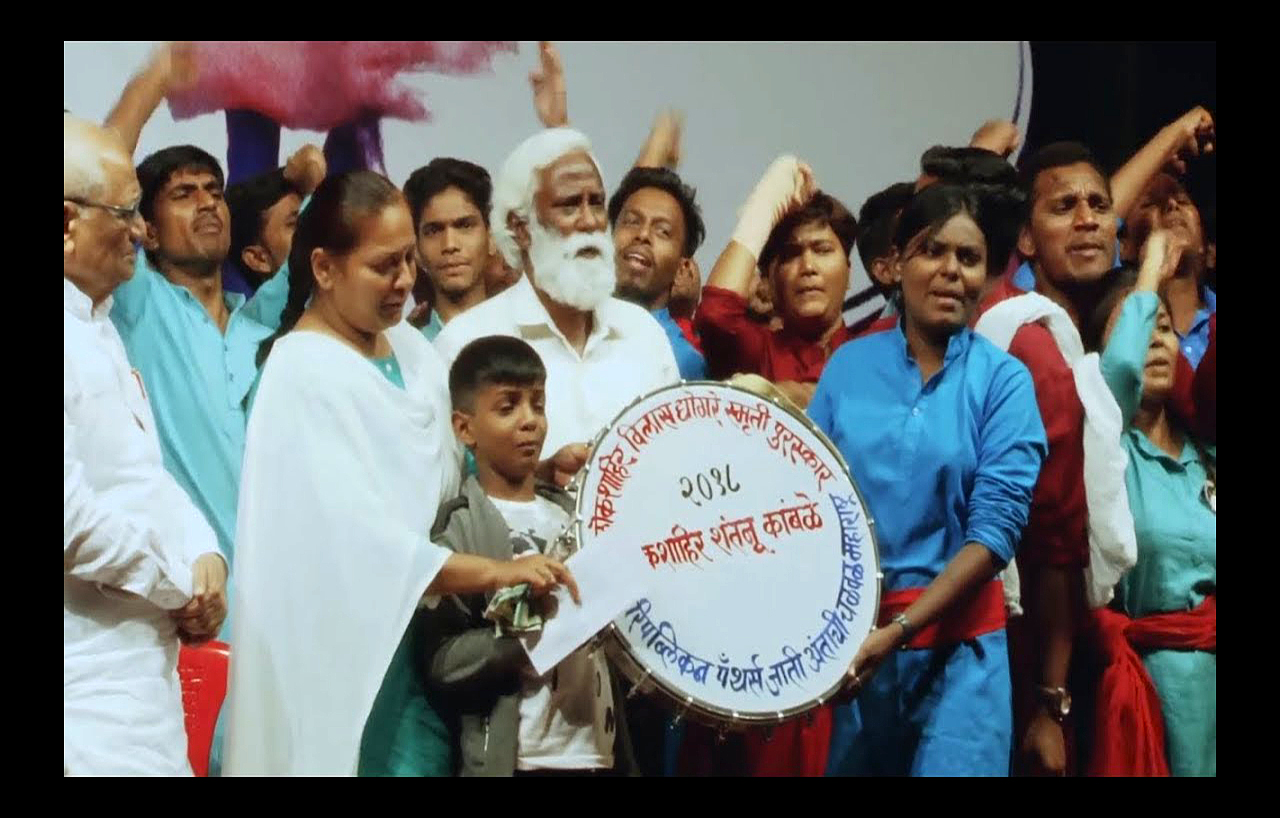

On 1st September, two of the significant anti-caste Marxist cultural organisations of Maharashtra – Samata Kala Manch and Shantanu’s own Kabir Kala Manch – organised a cultural protest performance at the Yashwant Natyamandir in Dadar in remembrance of their beloved Comrade Shantanu. Sewn with songs of Vilas Ghogre and Shantanu Kamble, the meeting saw an outburst of rage and anger against the caste order, particularly against the organised Manuvadi forces including the ones in power right now. The book ‘Revolutionary Lokshahir Shantanu Kamble: A Warrior on the path of equality and liberation’, published by the Republican Panther Publications, was released at the meeting. Shantanu’s wife Deepali Wagh spoke at the meeting, as did Retired Justice Kolse B.G. Kolse Patil (one of the official organisers of the Bhima Koregaon Elgaar Parishad), senior journalist Nikhil Wagle, and poet and activist Vira Sathidar. Talking about Shantanu’s reactions to the arrests of Dhawale and others, Deepali recounted, “He watched a debate on television shortly after the arrests of Sudhir Dhawale and other activists and was distressed. He said the present environment was scary and we would perish if we didn’t stand together.” Talking about the investigating agencies of this country and their history of ‘legalized’ violence on dalit, minorities and adivasis, Justice Patil described the CBI, functionally, as nothing more than “a wing of the RSS”. The speakers also brought up the role of investigative agencies in Gujarat after the post-Godhra pogrom – how investigative/legal processes were subverted, perpetrators were not only shielded but in fact rewarded with even greater powers, and how the ones that led or helped the investigations, were hounded, punished and at times eliminated. Incidentally, one of the other official organisers of the Elgaar Parishad, Retired Justice P B Sawant, a former Supreme Court judge, was a member of the People’s Tribunal which conducted inquiries in Gujarat in March-April 2002 after the post-Godhra riots. Justice Patil recounted the history of the SIT ignoring the Tribunal’s findings, subsequently letting Narendra Modi off the hook citing lack of “prosecutable evidence”. “Without political and cultural resistance, no hope should be nurtured about getting justice from any of the investigative agencies when it comes to the dalits, minorities and adivasis of this country”, he said.

Meanwhile, Shantanu’s body has to lose the battle, Sudhir Dhawale has to live in solitary confinement, the word “Dalit” itself gets black listed by the Government. Why do artists like Shantanu end up unnerving the state? Is it because they connect with people at their deepest levels of consciousness, and thus have the power to avalanche into a mass war-cry against the system? As in Shantanu’s call to the youth to fight repression, “Palu naka, duniya saari badla”. Or is it because they point out the hollowness of our so called “freedom” and raise chilling questions that the powerful have tried silencing for thousands of years?

Upaashi jhulyat bhavishya deshache jhoptaya (Hungry in the cradle, sleeps future of the country)

kon shahir randcha gaane azaadicha gaatoya? (Which bastard poet is singing songs of freedom?)

Is it because they paint the ugly, dark side of Indian social life with brutal honesty?

Gaavacha kondwaada tutlach nahi (The cattle pen in the village still remains)

Dhoravani jagne he jaatichya paayi (We’re treated like animals in the name of caste)

Gaavamadhye ek gaav gaavatach nahi (A part of the village has never been its part)

Pashusaathi pashu-daya aamhasaathi nahi (Compassion for the cattle, for us you have none)

Or is it because of the outright open challenge to fascists in power?

Vichaar-hatyaaranna aata paajlave lagel (It’s time to light up our ideological weapons)

hya Nazi bhatanna aata rokhave lagel (We’ll have to stop these Nazi Brahmanical forces now)

tyanna Hilter sarkhe aata thokave lagel (They’ll have to be killed like Hitler)

Aamhi bandacha ishara tumha detoy… (We are signalling a revolt…)

The case of Shantanu (and many of his colleagues who were persecuted by the police only to be found innocent later by the judiciary) is a piece in a larger pattern illustrated further by the continuing arrests of activists – it outlines the state’s response to anyone speaking out against systemic atrocities. Shantanu portrays this brilliantly in his satirical song, “Khara bolna paap aahe, Naxal tharavla jaashil” (It’s a sin to speak the truth, you will be labeled a Naxal). However in spite of the brandings, the arrests and the deaths, the shahir lives on through his shahiri, continuing to inspire future generations to take on a fundamentally unjust system, continuing to strike fear in the hearts of the oppressor.

This article is based on:

1.Revolutionary Lokshahir Shantanu Kamble: A Warrior on the path of equality and liberation (2018). Republican Panther Publication, Mumbai

2.The ‘Shahiri Powada’ in Maharashtra and its usage in contested identities and ideologies

3.Shades of repression by Aritra Bhattacharya

Aisha Kawalkar is a researcher in education. Translations of Shantanu Kamble’s poems are by the author.