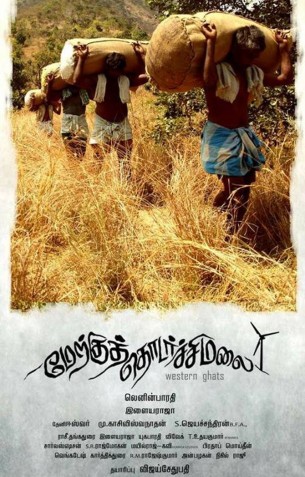

‘Merku Thodarchi Malai’ (Western Ghats) – a Tamil film that got released this year – speaks of complex questions around the personal and the political within the working class movement. Writes Chandrika Radhakrishnan.

“But looking at these things as a whole, it is evident that this does not depend on the will, either good or bad, of the individual capitalist. Under free competition, the immanent laws of capitalist production confront the individual capitalist as a coercive force external to him.”

– Capital Volume I

The Tamil film ‘Merku Thodarchi Malai’ (‘Western Ghats’) has captured the hearts and minds of the audience in its realistic portrayal of working class communities in the margins. It is set among cardamom plantation labourers along Tamil Nadu-Kerala border. This is a community that barely survives against the impacts of mainstream ‘economic development’. The film is essentially a character study of how individuals (both those who profit and those who survive) play their part wittingly and unwittingly in reproducing the exploitative relations of production under capitalism. But it also has something more important to say about those institutions and individuals that promise the alternative.

The story follows the aspirations of Rangasamy, a plantation labourer, who sets out to acquire a farming land for his personal economic well-being. He is helped by various members of the community including the owners of the plantation with whom he maintains cordial relations. There is a strong union in the plantations led by a communist trade unionist, Chacko, who ensures that only unionized workers are employed in the plantation.

While Chacko is able to thwart any attempt to use non-unionized workers, a new owner sets about actions in motion to use non-unionized workers. This increases the antagonistic relation between the union and the new owner and results in the murder of the owner and a communist leader, who is in cohorts with the owner, by Chacko, Rangasamy and other workers. Chacko, Rangasamy and the workers are imprisoned. To keep themselves afloat, his family is forced into debt with a trader, who sells them seeds and fertilizers. The trader who then also becomes a real estate broker, forces Rangasamy to sell the land to repay the debt. Rangaswamy is forced to go as a wage labourer to the very land that he used to own once.

While Chacko is able to thwart any attempt to use non-unionized workers, a new owner sets about actions in motion to use non-unionized workers. This increases the antagonistic relation between the union and the new owner and results in the murder of the owner and a communist leader, who is in cohorts with the owner, by Chacko, Rangasamy and other workers. Chacko, Rangasamy and the workers are imprisoned. To keep themselves afloat, his family is forced into debt with a trader, who sells them seeds and fertilizers. The trader who then also becomes a real estate broker, forces Rangasamy to sell the land to repay the debt. Rangaswamy is forced to go as a wage labourer to the very land that he used to own once.

The film exposes in its own understated style, the daily anguish of those whose lives are always controlled by others. The emphasis in the film has been on the representation of the processes of accumulation, so much so that as spectators, we cannot find one individual to blame. The everyday relationships between the exploiters and exploited are intertwined in a way that it becomes difficult to see the power relations that need to be challenged.

For instance, the film establishes through a long narrative, the complicated relationship between the protagonist and other stake holders – such as the plantation landlords, the plantation supervisors and Chacko – the union leader. In the plantations, where the workers are strongly unionised, it is the union leader who decides, on behalf of the workers, who will work and where. These are well captured in scenes where Chacko sends workers back home because they don’t have work and stops workers on their way to the plantation taken over by the new owner because the owner is not willing to engage with the union.

The control of the union in the plantation production is also visible in the scene where the supervisor is made fun of by the workers when they demand food and other kinds of perks during working. This provides a moment of lightheartedness in the narrative. What emerges is that the union has replaced the supervisor in the production process, but has left the larger structures that keep capitalist mode of production unchallenged. The film itself does not establish any actions by the union in dismantling the social relation between the capitalist as owners of means of production and workers as the users of means of production.

What this ends up revealing is that, while the film is about workers, there is no working class in action, especially if we attempt to reflect on the actions of Rangasamy in this context. Through the long narrative at the beginning of the film, it is clearly established that Rangasamy has very cordial, respectful and an equidistant relation with both his employers and Chacko, the union leader. He is seen taking orders respectfully from the owners, meets Chacko on the way, takes his work orders and does both diligently. It is the very same owners of the plantation, who come forward to help Rangasamy, by way of providing monetary help in buying his land. That these owners are good in their heart is shown in the way they deal with Rangasamy. The film attempts to show, even in situations of dire exploitation, personal relationships can and do exist between those exploited and those in power. At no point, Rangasamy turns to the union for his access to such crucial life-sustaining resources, and hence union has no place in such crucial decisions workers make in their life.

Even the unionized workers show no independent initiative of actions, whether it be when the owner moves to replace them with non-unionized workers or when they are evicted from their homes after transfer of the ownership of the plantation. It is only Chacko’s appearance that spearheads actions to stop and challenge these deeds. In the film, it is Chacko who is politically educated, and not the workers.

That Chacko is politically educated through the everyday practice of engaging with workers is obvious, as he the one who is attuned to the workers’ needs. When there is a proposal to lay roads in these terrains, he articulates the adverse impact of laying of road on employment of workers. However he finds opposition not from those who would profit from this move but from his own party leader, who is in favour of the laying the road as an inevitable process of development, in which workers will find other employment.

The film is unable to explain why two individuals representing two institutions of the same ideology are on the opposing spectrum in evaluating the same phenomenon. While the film conveniently ties the party leader (who sees it as anti-development) to be in collusion with the bad capitalist, what it exposes is that there is an understanding of the notion of “development” among the communists that dovetails into one that is held by the capitalists and the communists end up adopting the same mode of production in an effort to take forward this form of development. If Chacko is the communist, who is hard working, well-intentioned and a politically motivated worker, but unable to see the limitation of the existing union process becoming a mediation between capital and labour, then the party leader is also one who is unable to visualize party work beyond mediation between the state and working class. And both the union and the party become separate spheres of insulated political work within which no mutual sharing of experiences take place, thus preventing the formation of other forms of working class politics.

At this point, the union gains a certain kind of militancy due to an oppressor, who is willing to do anything to keep the power relations intact. This leads to Chacko and some workers, including Rangasamy, killing the party leader and the capitalist. It is to the credit of Chacko that he sees the extent of powerlessness of the situation that moved him to this action. This is not only because Chacko is a good individual but also he is an embodiment of an experience that comes from direct engagement with everyday realities of workers’ lives and struggles.

However, the real tragedy happens when Rangasamy transfers the land to the trader Logu who forces him to give up his land for the debt acquired. Logu is a constant presence in the film, silently working on establishing his trade through opportunities made available in the region. His character is the most ambivalent where the ‘goodness’ and the ‘badness’ of other characters are established vividly in the film (Malayalam Manorama used the words ‘Good, Bad and Ugly’ to describe the film, an apt description.) He is also the most visible beneficiary of the road laying project supported by the party leader, while he himself does not push for it. None in the community is able to deconstruct the ways of Logu, the trader. The most poignant scene is when Rangasamy is led meekly by Logu’s associates to sign away his hard earned land for the debts he has accrued.

The film is a telling evidence on how the union has not been able to capture the minds of workers and other members of the working class in redefining the social relations. Even when the workers accept the relevance of the union and appreciate the leadership, the union is unable to reshape the social relationships of production based on mutual solidarity amongst the working class. And differentiating the personal from the structural becomes difficult but more importantly, when dealing with systemic reproduction of oppression and exploitation through known members of community.

The left unions in real world are engaged in the mammoth task of developing collective strength of workers to ensure collective rights in a period when the state and the capital are waging a relentless attack on workers. The militancy of working class movement, in direct challenge from the capital, is visible in Pricol, Maruti etc. But when capital moves to co-opt through process of conciliation, the unions unwittingly become a tool of capital’s process of production. In an effort to convince workers of the strength of union, successful collective wage bargaining becomes the measure and excessive production targets, outsourcing are accepted (even if negotiated) which only strengthen the existing power structures (This, however, does not mean that the unions that adopt these strategies are pro-capitalist). Everyday hegemony of capital in shop floor is hardly engaged upon, which places workers at the mercy of the capitalist process. Issues of safety, hegemony by supervisors and HR managers are converted to compensations and legal fights, with no challenge to the process of production by developing and strengthening worker’s collective processes. And where the owners are seen to be ‘nice’, these lines become further blurred, that the communist leaders are forced to even engage on behalf of them, as was seen recently over accusation of idol theft by TVS group owners.

The shackles of capitalist control over production relation cannot be challenged unless other forms of institutions that promote material and social solidarity amongst workers are evolved by workers themselves. The working class members cannot be left to the mercy of the various representatives of the system, be it the supervisor, managers, owners, lenders, landlords and the politicians and expect to challenge the system continuously on the basis of ideology alone. That is why feminists coined the phrase ‘personal is political’ when they sought to define the patriarchal structures underpinning relations in institutions such as families. It is high time that the trade union movement, too, makes this slogan its very own, if it intends to change the power relations in production.

Chandrika Radhakrishnan is an IT engineer based in Chennai and an editorial member of Thozhilalar Koodam.