The Dwarf, the Girl and the Holy Goat is a new novel for children published last month by Hachette India. Cordis Paldano, the author, currently based in Chennai, is a versatile writer and theatre artist, wearing several hats. The novel—witty, sensitive, political in a very contemporary manner and every once in a while obscurely crazy—falls under a rare genre of children’s book written in English in today’s India. In an email conversation with GroundXero, Paldano shares some of his thoughts around writing and reading children’s literature.

The Dwarf, the Girl and the Holy Goat is a novel for children by Cordis Paldano—a writer, theatre actor and teacher currently based in Chennai. The book has just been published by Hachette India. It is an adventure-story of Inaya—the Girl, who loses Munni—the Goat—to a corrupt policeman. Though she literally loses Munni to the policeman, as the story unravels we see how in fact the corrupt socio-cultural landscape in their country (or ours!) is truly responsible for her loss. It is Charlie—the Dwarf, the circus-clown (an unlikely hero for a damsel in distress in real life and hence so powerful in the narrative, as seen in the Tyrion Lannisters of the popular literary world), who joins this adventure and helps Inaya out. The two brave ‘little people’ come to know each other at the risk of their life, livelihood, but most interestingly their ego. A careful play with their emotional frictions is one of the components that makes the book complex, although it is a kind of complexity identifiable by children. The other explicit point of complexity is perhaps not so easily identifiable for the present target readership of this book, namely, the metaphor of imposing ‘Holiness’ on animals by right-wing forces in order to oppress and eradicate minority communities and the politics around it. However, whether familiar with that politics or not, the villains are so deliciously classic in this story that the children are unlikely to miss the suffocating tension created by their treachery and notoriety. The book is a major mouthpiece of girl-power as well. Inaya—an Arabic word, implying solitude, kindness and grace—begins as a poor, helpless creature. But as the story goes forward, the readers will surely find many hidden qualities up her sleeve—at least as many as Charlie the trapeze-clown has. Often breaking into the form of stories within stories, The Dwarf, the Girl and the Holy Goat is a rare book for children that comes with a social message, but does not dilute either the message or the sincerity and understanding towards a child’s mind, which is absolutely necessary for exploring the genre of children’s literature.

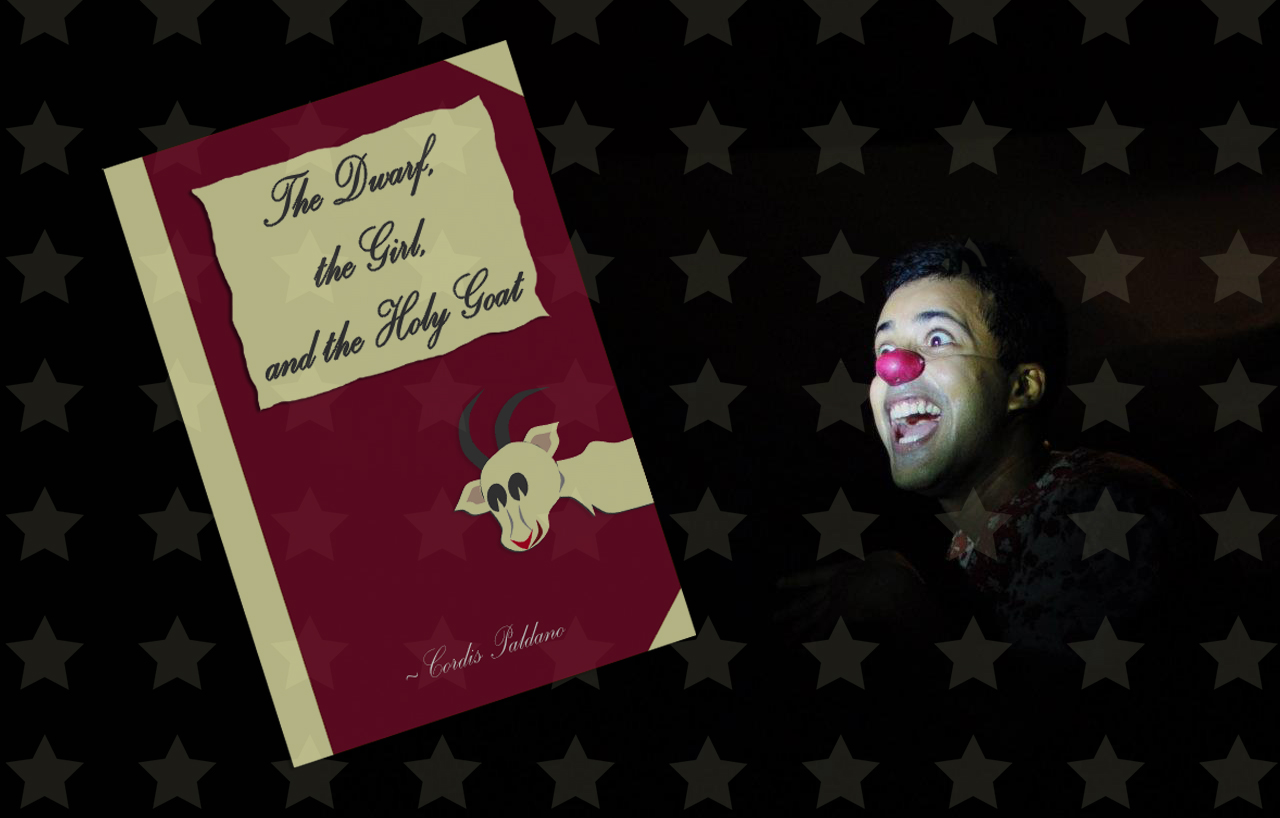

Cordis Paldano (Image courtesy: The Aalaap)

GroundXero: Is The Dwarf, the Girl and the Holy Goat your first novel? In particular, is it your first novel for children? Tell us a bit about your background as a writer.

Cordis Paldano: Yes, this is my first novel. I’ve written on an ad hoc basis for the theatre over the past ten years but this is the first time I’ve ventured into prose fiction.

GX: Tell us a bit about the process of writing this book. How did you get the idea behind the book and how did you proceed with the idea? Was the entire story pre-planned, or did it develop as you wrote it?

CP: I don’t know how the story came to me. I’ve been wanting to write something for a long time. And then after ten years of theatre and one intensive year at a University, suddenly I found myself alone in a room, with no theatre troupe to belong to, no play to rehearse, no scheduled performances… And I got so bored and desperate that I finally managed to write something after all.

Unlike some writers, I knew what was going to happen in the story before I put down the first word. I guess you could set out on a journey without any clue as to where you’re headed but then, what if you end up somewhere you don’t like?

GX: You have been an accomplished theatre actor. How does that influence your writing? Especially in terms of writing for children…

CP: Unlike novels written for older people where the quality of the writing tends to take the upper hand, children’s literature places a greater emphasis on the narrative arc. And indeed, that is why I chose to write for children – because structurally, it is the literary form that most resembles dramatic works.

Having worked professionally as a theatre actor does make it easier to come up with plots and characters. The flipside of course, is that theatre artists are notoriously undisciplined whereas there’s no way you can be a writer without some discipline and a work ethic… You could be a poet perhaps but not a prose writer.

The other great advantage of having worked in theatre is that you learn to keep your expectations low; anyone and everyone who has worked in a creative field, knows that in the arts, either you make a fortune or you make nothing… what’s impossible is making a living.

GX: The novel begins in the first person by a minor character in the story (and your next novel has the same form). It seems an interesting interpretation for me as a reader that you see yourself as the narrator somewhat detached from the main characters, and yet not detached enough from the story itself, and hence you place yourself as a minor character, as an ‘introducer’. Is my interpretation totally wrong? How emotionally detached or attached do you feel from the main characters as well as the story?

CP: Well, I don’t identify with my characters but emotionally, yes I am strongly attached to them. Not to the story, or at least not as much. I focus on the characters and what they want, and it is the characters’ job to bring the story along with them. That being said, in action-packed tales, characters do tend to be a bit shallow and this novel is very much centered around action.

Your interpretation is pretty accurate. Well, the narrator has to be somewhere! If he is not on stage then he at least better stay in the wings to introduce the main characters as they walk past him… (rather than watching it all from an omniscient perspective.)

GX: There is an obvious reference in the book to the ongoing horrifying politics and violence around the cow-ban and Muslim-lynching. Why did you choose to use ‘goat’ instead of, or rather as a symbol of ‘cow’? In general, in your experience, how do you feel children react to symbols as compared to ‘reality’?

CP: Not just children, adults too, we’re all creatures of meaning. In fact, we perceive meaning far before we even get a glimpse of the underlying reality.

Symbols are packed with meaning and so, symbols are nothing more than the means through which we communicate reality to each other. In that sense, even the cow is a symbol. What does this symbol mean? For centuries it stood for goodness, abundance and the sanctity of all life. But the meaning of a symbol is like a story written by a group of people. Another group can come along and write a totally different story and the meaning of the symbol changes. I was not interested in entering a debate on the utility of the cow. I am more interested in the politics of hate – how some groups hijack symbols and capture power. The examples are all around us: the swastika for millennia only meant auspiciousness and prosperity. The khadi cap used to symbolise honesty and simplicity… can you believe it? Even the Ram Janmabhoomi Yatra, its symbolism is eerily similar to Gandhiji’s salt march of 1930. Both set out from Gujarat on a quest for justice, in defiance of the law. One, a river of white, another, a river of saffron. Both leave indelible marks on our collective psyche and alter the story – what India means, what India stands for.

The left and the right, the liberals and the communalists, we’re all alike in that way – we’re all trying to rewrite the story, we’re all trying to capture the symbols we can, while trying to shoot down the symbols we can’t. It all comes down to a philosophical difference. What are the beliefs that are driving us?

The far-right for example, capitalises on the cow’s vulnerability and its suffering, to imply the existence of predatory forces aka Muslims that need to be subdued. But liberal Indians are doing pretty much the same: they point to the vulnerability and suffering of a minority community to imply the existence of predatory forces aka the vigilantes that need to be subdued. But as they say, the devil is in the details… The liberals are motivated by the belief that all human life is equally precious whereas the far-right is promoting a hierarchy in which a human life is sometimes worth less than a cow’s.

GX: This is a continuation to the previous question. Do you feel the necessity to inform children of real-life violence? You do bring in several references to violence in this novel through the dialogues of the corrupt policemen and thuggish political leaders and cadres. The same can be said about the stories within the stories, which often talk about war, caste-conflict and death.

CP: Oh yes, children need to be informed about real-life violence. In an appropriate manner of course. Too much exposure to violence and the child will be traumatised. Too little and they’ll be incapable of contending with the world when they grow up – the world after all is an incredibly violent place and we are an extraordinarily violent specie, as has been attested over and over again over the course of the twentieth century.

In that sense, violence is inherent to humanity and anyone who has ever worked in a school only knows that too well: leave a bunch of children unsupervised and they’ll inevitably start hitting one another. But leave them to sort it out on their own and they’ll soon learn to manage conflict and to form alliances. Educators and parents should never aim for omnipotence. It comes at the terrible expense of making the child weak and dependent on an authority figure.

GX: For that matter, how necessary is it for you to place your novels for children in the contexts of current socio-political issues? Your next novel too touches upon such issues…

CP: It’s not necessary for me. Well, I would like for children to be able to explore their current fears and insecurities through the novels they read. Sometimes these fears are nested in current socio-political issues and sometimes they’re not. The ideal book of course must have universal appeal but that I think is to be achieved not by shying away from socio-political issues but rather by focusing on a particular issue and exploring basic human concerns that we all share.

GX: You address various different socio-political questions. Not just the cow-ban and the politics around it, but also the politics around otherization of certain factions of the society, women’s empowerment, corruption at various vocational spaces, dictatorship, war and even empathy to animals to some extent. Was this political intervention planned or did it come naturally – as these problems are naturally integrated to our everyday lives?

CP: Oh no, it wasn’t planned at all… I never set out to become the Arundhati Roy of Children’s Literature. That is just incidental…

GX: In general, how do you think children comprehend the notion of ‘good people’ and ‘bad people’? (The question arises also at the point when the villain start abusing his followers, whereas, you hint, they were bad because they were asked to be bad by their leader)

CP: Without going so far as to say that a child’s view of morality is black and white, I will nonetheless stake the claim that black and white characters do hold great appeal for young readers. Look at the most memorable villains from children’s literature – Sauron and Lord Voldemort (though the latter comes with a back story of a sort) … not an ounce of goodness in them, not even the glimmer of the slightest virtue. If they existed in reality, they would be shunned and have no followers whatsoever because they’re cruel to everyone, even to their allies. And yet in fiction, they work brilliantly because they are the archetype of absolute evil and we are, all of us wired to create, perceive and react to such archetypes. This human mistrust and fear of the archetypal evil other and our proclivity towards the archetypal prophetic figure, is exactly what enables some bigots to control large sections of the population. Of course, nothing really is black and white, but it isn’t always so obvious. The best authors of course, have always created characters that are morally complex.

Cordis Paldano as a theatre actor (Land of Ashes, Indianostrum Theatre)

GX: You speak of ‘Inat’ – being consciously alive and positive even in the direst situation. You applaud individual defiance over collective defiance. In your everyday life, is that how you situate yourself as a political person and a political writer? When you work with children, how do you see the notion of individual defiance affecting them over the collective?

CP: I discovered ‘Inat’ and the remarkable story of how the Sarajevans stood up against war, when I visited Bosnia a few years ago. That was an instance of collective resistance and I hold it in equally high regard. There is something intrinsically beautiful and noble about a bunch of people holding hands with each other and standing up for what they believe to be a just cause. But of course, what people are doing when they come together is that each one of them surrenders his or her own individual story so as to be able to participate in a larger, more exhilarating collective story. But stories need authors, hence the thirst for a leader in every crowd. And the author could be one like Gandhi or someone like Hitler.

In my everyday life, I don’t particularly value the individual over the collective even though it is tougher and requires more courage to stand up as an individual than to do so as part of a group. But you’ll see that sometimes individual defiance is for a good cause and sometimes it isn’t… what matters is what you’re standing up for. Look at Aung San Suu Kyi… she’s always been a maverick. First she defied the military junta and now she’s defying international opinion… but those are two different stories entirely.

When it comes to children, I do believe that a large part of education is actually about learning to control your id-ridden impulses. So if you think that you’re right and everyone else is wrong and you’re five years old, then seriously, appreciation is the last thing you deserve. After all, individual defiance is pointless if the person does not have a strong internal moral compass and I think it was Piaget who first pointed out that moral reasoning happens only in stages – the morality of children till the age of ten, is controlled by external factors. (This is not to say that kids are incapable of “moral” behaviour.)

GX: Do you have a series in mind with these characters?

CP: Not really. But why not?

GX: This is not a question, but an admission of appreciation. The Bakra Boys Anthem is one of the funniest songs I’ve read in children’s literature. Once the book is published, we must have a real song out of that! For now, can you share it with us?

CP: Here it is.

The Anthem of the Bakra Boys

Oh, we’re the true sons of the soil,

We’re the purest of the pure,

And if anyone disagrees then

We will thrash them, that’s for sure.

We’re the true sons of the soil,

And this land so much we love!

So, Outsiders, keep your heads bowed,

Or we’ll thwack you from above!

Our land is rich with many creatures,

Best of them all is the goat,

Purer to us and more precious,

Is she, if white is her coat.

Oh, the white goat, oh, the white goat,

She is holy to us all,

For her we shed tears and we cast votes,

Then we roll up our sleeves and brawl.

If you kill goats, we will kill you,

If you beat goats, we will beat you,

And if you steal milk, from the goat’s kids…

That’s… well… erm… what we all do!

For we’re the true sons of the soil,

We’re the purest of the pure,

And if anyone disagrees then

We will thrash them, that’s for sure.

(Excerpted with permission of Hachette India from The Dwarf, the Girl and the Holy Goat by Cordis Paldano; Paperback Rs. 299)

GX: How do you feel about the target readership of this book? For now, this seems to be meant for children from English-speaking, perhaps upper-middle class families in India and abroad. But how strongly (or if at all) do you feel the need of translating this book in regional languages and spreading it in regions where children might be able to identify with the problems of poverty and communalism more acutely?

CP: When I was writing the novel, it was not obvious to me that the book would eventually be published. I told myself that I was composing a story that I would someday be able to share with my own hypothetical daughter. So my target audience has always been that one child in the future – the social class and first language of my audience was irrelevant to me. Who the book is meant for is decided to a large extent by the way it is marketed by the publisher and for now at least, I have very little say in that matter. My only link to the publisher is my editor Vatsala Kaul and she is absolutely brilliant – both sharp as well as passionate. And so, I’m more than happy to just write and leave the rest to her.

That the story found its way into a book and is now available across the country, never ceases to amaze me. So I’d only be delighted if there were an endeavor to translate it into other languages and take it to more children. It would of course receive my whole-hearted support.