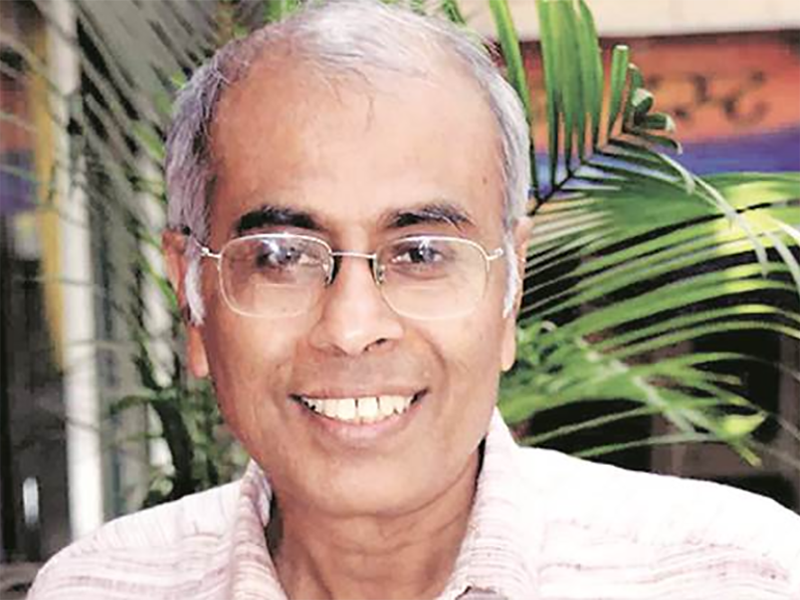

This year, August 20 – the death anniversary of Narendra Dabholkar – was observed as the ‘National Scientific Temper Day’. In Maharashtra, a week-long series of discussions, meetings and public lectures were organised across schools and colleges in the state, by scientists, educators and students from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Center for Science Education, IIT Mumbai, etc. The urgent drive seems to be about countering the organised ‘anti-science’ campaign gaining ground across the country in recent years. However, such ‘science awareness’ outreach efforts led by science research institutions as above quickly run into the deep troubled waters of a historic social conflict between ‘science’ and ‘faith’, reminding us of a sad and violent saga of alienation. What kind of questions should the modern Indian ‘secular’ scientist be ready to face before he or she begins to pose loud public questions about ‘faith’? Siddhartha Dasgupta writes.

This week has been observed across various parts of the country as the “National Scientific Temper week”. Not mandated by any Government circular, or Constitutional obligation, the science awareness programs organised across various schools and colleges by a loose network of scientists over the past one week were in fact in memory of a rather painful incident. On a 20th of August, 5 years back, rationalist doctor, social activist and author Narendra Dabholkar was murdered while on his morning walk, in the town of Pune, as some assailants fired four rounds of bullets at him from point blank range before fleeing on a motorcycle. Dabholkar’s killing marked a watershed moment in the steadily brewing social ‘outrage’ in this country against notions of scientific rationality. Since his murder, we have witnessed several other such assassinations – such as those of Govind Pansare, MM Kalburgi, Gauri Lankesh, and others who have worked through their lives against unquestioned submission to dominant ideologies.

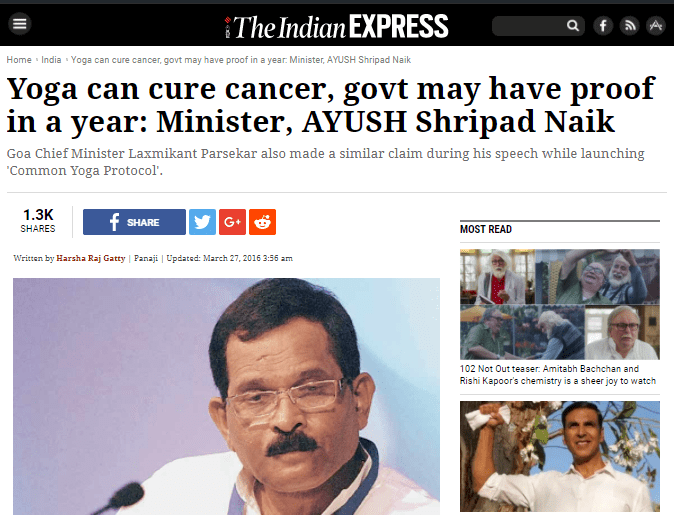

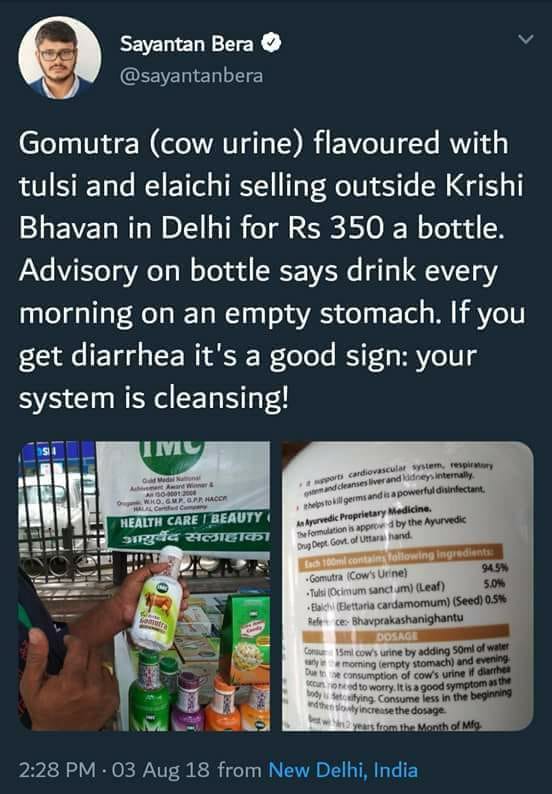

The murders however only form the tip of the iceberg. Over the past few years, we have seen a regular organised onslaught on the very ideas of rationality and science. Various statements and provocations from those in power – be it regarding plastic surgeries and nuclear weapons in ‘ancient India’, or the historicity of the so-called ‘Ram Setu’, or the medicinal aspects of bovine urinal discharge – and effective impunity to those who trade in such falsehoods, have put official seal of approval on such agendas. Ironically, such approval comes not only from politicians or religious spokespersons, but also from a significant section of the scientists themselves. For, many of the claims such as “Lord Ganesha (Hindu God with the head of an elephant and body of a well-fed man) testifies that ancient Indian scientists knew about plastic surgery” were shouted out by none less than the Prime Minister of the country, at a meeting of doctors in Mumbai, without a single doctor or scientist present there objecting to such a claim.

However, a section of scientists across eminent institutions in the country have since organised themselves in a bid to counter such a culture of “fake science” or “pseudo science” that seems to be rapidly engulfing the social realities of the nation. Marches for Science, regular public meetings, and workshops have been organised, and most recently, the “Scientific Temper Week” has been announced.

March for Science. Courtesy: The Hindu

This nation (and in fact the whole planet so to speak) has seen a clear spike in such concerted attacks on science, truth and rationality in the recent past, and much of these attacks are organised by political forces who have ideological roadblocks when it comes to dealing with ‘truth’ and ‘facts’. However, questions regarding ‘scientific temper’ and ‘scientific rationality’ are social questions – going far beyond the current regime, or those in power in the electoral sense. To take a brisk walk through the history of national leaders talking about science and scientific temper, here are a few important examples that represent a significant phase in Indian science at the policy level:

- In 1966, the Nehruvian era physicist Dr. Homi Bhabha said at a lecture he gave at TIFR, using gendered terms: “If a scientific outlook is to be made a part of the mental makeup of every individual, then clearly his education has to be molded accordingly.” Bhabha was one of the chief architects of a number of ‘premier science research institutes’ in the country, including TIFR, IISc, etc, and is broadly seen as the scientist who ushered in institutionalized modern science in post-transfer of power India.

- In 1976, under the PM-ship of Indira Gandhi, the 42nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution was passed, which among other things enshrined “Fundamental duty of every Indian citizen to develop scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”. It is hard to forget that it was under the regime of the same Indira Gandhi that millions of poor people in this country were forcibly sterilized as part of a ‘scientific drive’ to contain poverty.

- In 2001, PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee said at the 88th National Science Congress, “Our goal is to make India a leading scientific nation in the world in the new century that hinges critically on how successfully we take science to the people and create a stronger scientific temper in our society”. It is equally hard to forget that Mr. Vajpayee, as an RSS pracharak during the 1992 Babri Masjid Demolitions had famously celebrated the bringing down of a Muslim religious structure in the name of a mythical Hindu god, and who also was one of the ‘petitioners’ in perhaps the most high profile and politically significant law case in the Supreme Court of this country.

Indira Gandhi and A.B. Vajpayee are clearly examples of seasoned political operatives, who are not expected to pay any more than a lip-service to science. For now it is the example of Homi Bhabha that deserves more attention for a meaningful discussion. Bhabha talks about a “scientific outlook” that is to govern the mental makeup of every individual in this country. This begs the question: What is a “scientific outlook”? And this is closely connected with the question “What is Science”? While there is a historic and still ongoing epistemic debate about what science is, for the sake of this report let us agree on a ‘work in progress’ definition of science. For our purposes, let us assume that the following are the key tenets of what could be considered a ‘scientific’ theory or approach: Coherence and consistency with observed facts, a process of inquiry, falsifiability, predictability. Here, ‘falsifiability’ refers to the fact that the theory is up for tests and ought to be rejected when observed data is in contradiction with the postulates of the theory. ‘Predictability’ on the other hand means that a theory that aspires to be ‘scientific’ needs to be able to predict phenomenon.

While there is an ongoing epistemic debate about what science is, for our purposes, let us assume that the following are the key tenets of what could be considered a ‘scientific’ theory or approach: Coherence and consistency with observed facts, a process of inquiry, falsifiability, predictability.

A historic example of ‘falsifiability’ was when Newtonian physics could not explain certain optical phenomena observed during the eclipse. Turned out that it was Einstein’s theory of relativity that could eventually explain what was going on. Thus, Newtonian physics was ‘falsifiable’, and in a sense got ‘falsified’. This does not however mean that Newtonian physics is “false” and ought to be rejected. In fact, Newtonian physics explains correctly most of the physical phenomenon as long as they don’t involve extremely small (such as, sub-atomic particles) or extremely large (such as stars) objects, or objects moving at extremely high speeds (such as light). The theory of relativity however improves upon this, fills in the gaps that Newtonian mechanics misses, and in fact lays out a broader scheme of things where Newton’s physics is an approximation, and a pretty good one, as to what exactly is going on. Thus, ‘falsifiability’ in science allows scientific theories to constantly reassess themselves, and ‘correct’ themselves to arrive at a better approximation of the universe. “All ghosts in this room vanish as soon as the doors are closed” is an example of a statement that is ‘unfalsifiable’ for instance, till the time we have the means to detect ‘ghosts’ and their movements – it can neither be proved, nor disproved.

‘Predictability’ similarly is what is seen today when say NASA scientists predict the exact time and location of an eclipse, based on astronomical theories and observations. Predictability of the sciences is what allows us to ‘check weather conditions’ beforehand and decide whether to take an umbrella or not when we are stepping out of our homes. None of the above is to say either of the following: (a) that scientific theories are always correct and (b) that science can explain everything. In fact, (a) scientific theories are supposed to be always up for further research and correction, and (b) mathematically it has been proved that science can never answer ALL the questions that human beings can think of, when it comes to nature – in a way, mathematics and therefore sciences end up limiting themselves because of their own theoretical framework. Thus, a decent workable description of ‘science’ could be a knowledge system which is consistent with observed facts, which can be tested if needed, falsified if the observations don’t match (falsification then means either rejection of the concerned theory or corrections), and is able to predict phenomenon without having to necessarily wait for them to happen. This is what some of the scientists who are trying to defend ‘scientific temper’ are saying, in gist.

Assam Health min #HimantaBiswaSarma says people suffer from life-threatening diseases such as cancer because of sins committed in past which he called "divine justice"

— Press Trust of India (@PTI_News) November 22, 2017

On the other hand, let us take a brief look into the ‘opposition’ to science (at times equated with the phrase ‘Western modern science’), so to speak. Let us briefly turn to some of the key arguments of the so-called ’anti-science camp’:

- “Science doesn’t know everything, so how can science claim to falsify “my claim”?” – No knowledge system in this world so far can explain everything, be it science or be it astrology. But the question of falsifiability remains. If a claim is not consistent with observed facts, then it is clearly ‘false’. If, with every other factor under control, drinking of cow urine does not cure a cancer patient, then cow urine is not a cure for cancer.

- “I cannot prove that my claim is true. But can you prove that it is false?” – the ‘burden of proof’ rests with the one who is making the claims.

- “Science is always evolving. So it is possible that scientific proof for my claims will generate in future” – once and if there is a ‘proof’, surely the claim will have to be accepted, but not before that.

- “Anecdotal evidences” – Anecdotes are not statistics. Anecdotes are liable to the limitations of human memory and agency, because it is human beings who cite anecdotal evidences. “So and so astrologer’s such and such prediction about my life came true” ignores the possible fact that many other predictions of the same astrologer, or astrological rules he or she might have followed, would not have come true. Anecdotes are selective, and human beings are typically prone to selecting anecdotes that confirms their preconceived beliefs – something technically known as “confirmation bias”.

Courtesy: AltNews

This brings us to the somewhat fundamental question of ‘science’ versus ‘belief’. Is there no ‘belief’ in ‘science’? Is there no ‘science’ in ‘belief’? The second question is in a way well-addressed historically. Often we hear scientific rational explanations behind ‘beliefs’ that are distilled from accumulated human experience. Case in point: the ‘belief’ that curd is good for the stomach, was also scientifically verified after the discovery of ‘gut bacteria’ – the microorganisms in our stomach that help digest food, and are known to thrive on curd.

The question that is more relevant to us here is however, “Is there no ‘belief’ in ‘science’”? This is where the dominant scientific community seems uncomfortable. But here are a few examples: What convinces us that our smartphone or laptop won’t suddenly explode while reading this article? What convinces us that when we steer the wheel of our car to the right, the vehicle will also turn right? What convinces us that we would fall if we jump from the terrace of a high-rise? Is it true that the answers to the above questions necessarily have to hinge upon our ‘scientific’ knowledge about how “electrical and electronic gadgets work”, “car physics and mechanics” and “gravity”? Clearly the answer is no, and somewhere therefore we operate based on our “beliefs”.

“Is there no ‘belief’ in ‘science’”? This is where the dominant scientific community seems uncomfortable. But what really convinces us that our smartphone or laptop won’t suddenly explode while reading this article?

Among today’s physicists, the belief that there is a grand unified physical theory for the entire universe, tying the subatomic particles and the planetary bodies together under the same set of laws – the so-called “theory of everything” – is an example of a high profile ‘belief’ that warrants the spending of billions of dollars for research towards such ends. Till Einstein came along, physicists across the world ‘believed’ that Newtonian physics is the ultimate answer to any physical question. Of course, when scientists ‘believe’ in a theory, they are supposed to be open to the possibility of that belief being shaken with newer observations (to remind ourselves: falsifiability). But clearly, beliefs abound well inside science itself.

The question therefore, when it comes to ‘scientific temper’ and ‘rationality’ etc., is: is it necessarily a fight between ‘belief’ and ‘rationality’? Or is it somewhere else? Indeed, it would be a sad day if in order to act like a ‘rational’ being, one needs to undergo a probability calculation of “what are the chances that my laptop would explode” every morning, based on observed facts in history regarding laptops exploding, before deciding whether or not to switch it on. We usually do not operate like that, and any organised attempt at substituting ‘beliefs close to our homes’ with an ‘alien science from faraway’ is bound to fail. The point is, in other words, not to necessarily replace the idea of ‘beliefs’ or experiential knowledge, with hard mathematical science. The historic issue facing Indian science and its relationship with people at large, is in fact the constant and deliberate fudging of lines between scientific inquiry and faith – treating science as faith, and on the other hand attempting to prop up pure faith as science. While ‘science’ and ‘faith’ have never really been watertight mutually exclusive categories, the progress of the very idea of science itself relies on organised efforts to constantly distinguish ‘science’ from ‘faith’, even if it is known to be an endless endeavour. Deliberate state-sponsored blurring of these lines work precisely against this dialectic of scientific knowledge production.

Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) directors after offering prayers at the Tirumala shrine, ahead of the launch of the PSLV-C 39. August 31, 2017. Source: www.tirumalaupdates.com

In Europe, where scientific jumps, such as the ones due to Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein or Boltzmann (one of the first people to lay foundations for quantum mechanics, who had to commit suicide because no one in the science community would believe in his theory), always met with social reactions – both in opposition and in favour, though often not on equal terms. However in post-colonial India, western modern science (regardless of whether it’s correct or not, whether it is the only possible ‘science’ or not) has always been a state or corporate driven nation building project. Darwin’s ideas of evolution were always in fundamental conflict with any kind of creationism. However, it is only now that we are facing organised political Hindu resistance to Darwin’s idea in this country. So far, it was either quiet acceptance of evolution, through school science texts, or ‘eminent scientists’ spreading science to the ‘illiterate masses’, or attempts at accommodating the theory into Hindu mythology, such as in the stories of the ten avatars of Vishnu, a Hindu god. Modern Science in India has so far largely been a matter of belief.

Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) made significant contributions to the scientific revolution, specifically by making improvements to the telescope and by making astronomical observations that supported Copernicus’s findings. Galileo was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Roman Church because his scientific discoveries and theories went against claims put forth by religion.

What happened to pre-modern ‘Indian Science’? That is another tragic story. Like any other colonized society, south Asian science was clearly suffocated and attacked by the European colonial powers. Modern post-colonial Indian scientists ignored the scientific discoveries that happened before colonisation, leaving behind a fertile vacuum for the reactionary anti-science forces to come up with fantastic claims regarding a fabled ‘ancient Indian science’, such as plastic surgeries in the times of Ganesha (whenever that was), when neither plastic, nor surgery could have existed. It is ironic that there had been significant surgical progress in ancient India, for instance the works of Sushruta, which are seldom treated with any seriousness by those thumping their chests about “Ancient Indian Science”.

The business side of cow urine.

Though the current attacks against ‘Western Science’ are to a large extent organised because of serious political and business interests (something that deserves a separate focused piece), the unorganised mass approval and endorsement of such attacks are a natural fallout of this alienation that has been historically inflicted upon the people of this country in the name of Science coming from the ivory towers of science research, for instance the ones created by Dr. Homi Bhabha. All of these institutions have kept the majority of citizens of this country outside of their walls, with deliberate precision. The very idea that science research can and should be done only in ‘science research institutes’ and not in the liberal arts universities (unlike anywhere else in the Western world from where Dr. Bhabha drew his inspirations) – institutes that are somehow beyond the social and political guidelines governing normal Universities in the country otherwise, symbolizes this principle of exclusion by design. ‘Science’, ‘scientific knowledge’ and ‘scientific temper’ have been commissioned in these closed ‘utopias’, only to be then sold or distributed among the people outside. Funded by the Government and business interests, anti-people but ‘scientific’ (so to speak) economic policies have impoverished billions. For example one can look at the role of agricultural science in bringing agriculture to the verge of destruction (thanks to genetically modified seeds, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, etc.). Medicine research at best projected modern medicine as magic to people and at worst robbed them of the resources to be able to seek medical attention. One can find several such examples of this alienation and domination – all in the name of science, peddled by these institutions in a structured way.

Sushruta – Medical Pioneer of Ancient South Asia

It is not surprising therefore that in a country where untouchability has been a social problem for thousands of years, space shuttles, satellites and nuclear weapons seem to be more of an aspiration for ‘scientists’ than scientific innovations that would mechanize something like manual scavenging. What we are witnessing today across various quarters therefore, is not just a politically organised attack on ‘science’ and ‘scientific facts’ or ‘scientific temper’, but also a significant mass upsurge backing such efforts. A people who have for thousands of years been subjected to the tyranny of the ‘scientific’, without being given any access to science, seem to be revolting against the idea of science itself. This today has found the perfect leader among those in the echelons of social, economic and political power who have realized that they cannot hide their lies and crises anymore with any kind of ‘logic’, necessitating therefore an all-out attack on the idea of ‘truth’ and ‘fact’ itself – be it in Modi’s India or Trump’s America.

What needs to be done then? There is no clear answer to that, but just like intentional blurring of lines between ‘beliefs’ and ‘rationality’ are at the heart of the problem, the reactionary response of therefore propping up an imagined binary between ‘beliefs’ and ‘rationality’, with the aim of then Constitutionally confining ‘beliefs’ to the private and ‘rationality’ to the public, is not the solution either. The least that needs to be done is to undertake socio-cultural-political attempts to stimulate the debate regarding faith and science and understand the dialectic relation between the two, with the aim of fostering a cultural practice of ‘inquiry’, putting gold value on questioning and seeking evidence. Questions then are not going to be limited only to the ‘non-science’ or the ‘superstitions’ – questions will be raised against the ‘high science’, it’s institutions and it’s markets as well. And soon enough, questions about power structures in society and politics will follow suit. Unless the scientists who aspire to spread ‘scientific awareness’ are also prepared for such questions about power and accountability in general, unless they are willing to face questions regarding Saraswati (Hindu goddess of knowledge) worship celebrations at their own public-funded science research institutions, questions regarding running science research institutions on money essentially from the nuclear industry, or regarding non-implementation of reservations in these supposedly ‘public’ institutions, someone like Dabholkar’s dreams would only remain elusive.

Source: AltNews

Quite a pro-Science article indeed, which is fine. However I have some questions. Do all attacks on Science come from the scienceeducation-deprived Right wing? You think feminists, sociologists, Marxists, etc. do not attack science? Science is an activity carried out by predominantly upper caste Men (of course #NotAllMen do Science) Doesn’t Science have a caste-class character that makes it so dominated by Brahmins and Kayastas? Your article does not engage with Science at all. And further, it presents a very postmodern relativist position on “Belief,” thereby equating all forms of belief under one umbrella. To believe in Ambedkarite Buddhism is different from believing in Brahmanical Hinduism. Belief is political. And so is pseudoscience. Richard Feynmann the pervert (who was given a nobel prize for his contribution to the nuclear bombs) refers to Social Science as pseudo science, which is not surprising. And a lot of Sciencesevaks glorify the @$$h0le. Your article depoliticizes the act of belief and faith. It nicely speaks of Boltzmann who was pushed to commit suicide. However, your article does not suggest who is responsible, who should apologize. I don’t think the Scientific community who pushed Boltzmann to kill himself while appropriating his ideas, give two shits about his death. This is how science functions ideologically. When they are confronted with a Boltzmann (or Cantor, or Darwin) they troll sometimes until the person is driven to insanity or death. But after their ideas prove powerful and the scientists cannot but accept their theory, the scientists claim the martyrs as their very own while accusing other potential revolutionaries as nutjobs. Scientists need to called out for their bullshit rather than invited for a dialogue. You may say that #NotAllScience is bad, and the core of science lies some innocent curiosity and experimentation and all that happy phrases so often used to sell a commodity. Then why not break away from the institutions that bombed Nagasaki on 9th August 1945 and Marched in FAVOUR of science on 9th Aug 2017? If you think there are some positive aspects of Science then Science needs a protestant revolution, not a bunch of doctors of the Catholic Church (I’m using an analogy here). But Science won’t do that because Science is the lapdog of Colonization and global capitalism (Why was Darwin on that ship anyway?). And science needs to be called out for what it is rather than fixed for efficiency.