Soumitra Ghosh

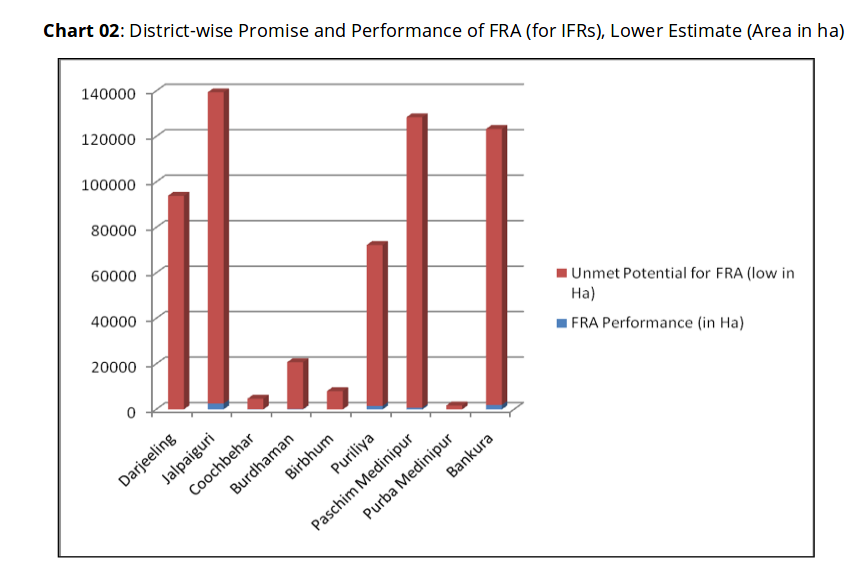

It is generally known by now that West Bengal has an extremely poor record of implementing the Forest Rights Act (FRA), which is meant to atone for the ‘historic injustice’ committed against millions of marginalized and rights-deprived forest dwellers in the country. While in some areas the implementation process has started haltingly and in a slipshod manner, consisting mostly of so-called ‘patta-giving’ (people were arbitrarily given dubious pieces of paper in lieu of proper land titles) intermittently spread over the last one decade, in other areas almost next to nothing has been done, as if the forest communities there do not exist. In the Darjeeling hills (now divided into two districts: Darjeeling and Kalimpong), for instance, nobody knows if there is an official process at all! Though there have been occasional initiatives to distribute claim forms (forms A and B; form C, which is for Community Forest Resource, doesn’t officially exist in West Bengal) and conduct ‘hearings’ and land surveys (particularly in Darjeeling Sub-Division), not much has resulted from these—not a single patta under FRA has been issued in the area, let alone recognition of community rights.

Which means that about 2.5 lakh (Source: HFVO press briefing in Siliguri on 3/4/18) residents of 165 forest villages, besides other forest-dependant people living in the tea gardens and revenue villages, in the Darjeeling Hills continue to be deprived of their rights. Though there was a strong movement on the ground, and people had started a process of self-implementation of FRA, official recognition of forest rights remained elusive. One reason which was sometimes cited was that the official process of FRA implementation could not start in the area because there were no functioning panchayats—ever since the Darjeeling area was constituted into an autonomous Hill Council (Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council or DGHC), later Territorial Authority (Gorkha Territorial Administration or GTA).

Courtesy: Aainanagar

In late 2014, 99 forest villages in the neighbouring districts of Alipurduar and Jalpiguri were converted to revenue villages through a gazette notification. In Darjeeling too, a fresh process seemed to have taken off, following a memo from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (23011/11/2013-FRA, dated 8 October 2015) clarifying that elected councilors of GTA could replace panchayat members so far as implementation of FRA is concerned. However, the process never bode any good for the forest dwellers—the district administration and the GTA authority taking interest in FRA simply meant that they urgently needed No Objection Certificates (NOC) from Gram Sabhas in the Teesta valley area for a host of upcoming development projects, all of which require forest land. Suddenly FRA became important, not because of government’s concern for forest rights—on the contrary, compliance with FRA is merely a statutory necessity, without which forests cannot be legitimately diverted. An uncertain amount of forest land needs to be diverted in the Teesta Valley for the proposed Sevoke-Rongpo railway track, besides widening of National Highway 10 (previously NH 31A) and 3 new Hydro Power Projects by NHPC. According to an estimate prepared by Himalayan Forest Villagers Organisation (HFVO), the projects would affect about 40000 persons residing in 24 forest villages. These figures are tentative; an exact assessment of the potential cumulative impacts of the projects cannot be done unless more information is available.

Meanwhile, pressure on the forest dwellers mounts. For the last two-and-a-half years, villagers in the area have in turn been ‘approached’, lured and threatened, by the authorities and the local political strongmen, so that the much-coveted NOCs from the Gram Sabhas can be obtained without much fuss. Unfortunately enough, neither the state government and GTA authority nor the political parties of the region seemed to take any real notice of the justified apprehension and demands of the villagers. Though the new chairperson of the present GTA went on record stating that the Sevoke-Rongpo railway track would affect no forest village of the area, the district administration of Kalimpong has officially convened a series of Gram Sabha meetings of 17 forest villages in the Teesta area vide back-to-back notices issued by the Block Development Officers at Kalimpong 1 and 11 Development Blocks, both dated 12/04/18, with the declared agenda of “Granting of ‘No Objection Certificate’ to Railway Authorities to use and occupy forest land for the purpose of construction of Sevoke-Rongpo new broad gauge railway lines to the North Frontier Railway”. Apparently, the notices follow a GO dated 03.03.2017 from the Department of Panchayats and Rural Development, Government of West Bengal, ‘empowering’ the Block Development Officers to convene meetings of Gram Sabhas so that such ‘No Objection Certificate’s can be issued.

The Gram Sabhas and HFVO have decided to boycott such meetings, rightly pointing out that the law permits neither the Department of Panchayats nor Block Development Officers to convene Gram Sabhas or dictate agenda for those. More importantly, they have collectively decided that the question of issuing NOCs to development projects including the railway line simply doesn’t arise before all their rights are duly recognized, according to the provisions of FRA.

Who is in control, really? Who decides what would be done with forests? The FRA gives the Gram Sabhas adequate power to decide whether an activity might harm the forests and culture of communities, and, if necessary, to stop it. More importantly, the Gram Sabha is free to adopt any measures it dims fit to conserve forests and biodiversity. The Supreme Court in its Niyamgiri judgment (which needed 12 gram sabhas of Dongria Kondhs to take a decision on whether diversion of forest land for Bauxite mining would affect their spiritual and cultural values—the gram sabhas unanimously decided to deny permission for mining) reiterated that the Gram Sabha-through its duties and powers under Section 5 of the FRA–at the village or hamlet level (and not the Panchayat) as defined in the FRA decides whether forests can be diverted at all. The FRA actually has no provision for handing out NOCs.

The Forest Rights Act 2006 guidelines issued by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, state clearly that “the State Government should ensure that all diversion of forest land for non- forest purposes under the forest conservation Act 1980 take place in compliance with the instructions contained in the MoEF’s letter dated 30.7.2009 as modified on 30.8.2009.” Point A of the Ministry of Environment and Forest’s letter dated 30.7.2009 requires “ a letter from the State Government certifying that complete process for identification and settlement of rights under FRA has been carried out……”. Point C of the same letter states that, “a letter from each of the concerned gram sabhas, indicating, that all formalities/processes under FRA have been carried out and that they have given their consent to the proposed diversion and the compensatory and ameliorative measures if any, having understood the purpose and details of the proposed diversion”.

Without complying with any of the above, the state government has initiated an illegal process of obtaining NOCs from Gram Sabhas, without the informed consent of the affected Gram Sabhas and without recognising forest rights.

The Sevoke-Rongpo rail project is supposedly the ‘dream project’ of Mamata Banerjee, Chief Minister of West Bengal. During her recent visit to Sikkim, Mamata and Pawan Chamling, the Chief Minister of Sikkim, made a joint statement in support of the project. Following this Binay Tamang, Chairperson of GTA, also supported the project, which, according to him, would pass through tunnels and won’t affect forests and forest villages.

Courtesy: Indian Express

Not surprisingly, it is being heard that the District Magistrate of Kalimpong is in favour of using force and summarily evicting the villages unless the NOCs are forthcoming. The threat of eviction was there before the railway project appeared on the scene—for years the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Limited (NHPC) has been trying to clear the roadside forest villages located around their hydro power project Teesta Low Dam-III. Dam-building and road-widening work has already affected the unstable landslide-prone hills of the Teesta gorge, submerging and destroying forests, making the communities yet more vulnerable.

The forest communities of North Bengal have been waging a grim battle for their rights for the last two decades. The Teesta story is a part of that continuing saga. It also illustrates how easily and brazenly the state subverts its own laws.